🧀 The King of Cheeses

Hey everyone, Chef Bari here.

I want to talk to you about something close to my heart, something that’s been a part of my kitchen for my entire career: Parmigiano Reggiano.

We all know it, we all love it, but I feel like we don’t always know its story. And trust me, it’s a story of passion, patience, and a lot of love that goes back almost 900 years.

A Taste of History

Picture this: It’s the Middle Ages in Italy. Benedictine monks—these incredibly hardworking and clever guys—had a problem. They had all this amazing milk from their cows, but no refrigeration. They needed a way to make it last.

So, in the fields between the towns of Parma and Reggio Emilia, they created something magical. Using the local salt, their cows’ milk, and an incredible amount of patience, they invented a massive wheel of hard cheese that wouldn’t just last for months—it would get better with time.

They created the first Parmigiano Reggiano. And the amazing part? The recipe we use today is almost exactly the same. It’s a taste of history in every single bite.

The Great “Parmesan” Lie

Okay, let’s get something straight, because this is a big point of confusion, especially here in North America.

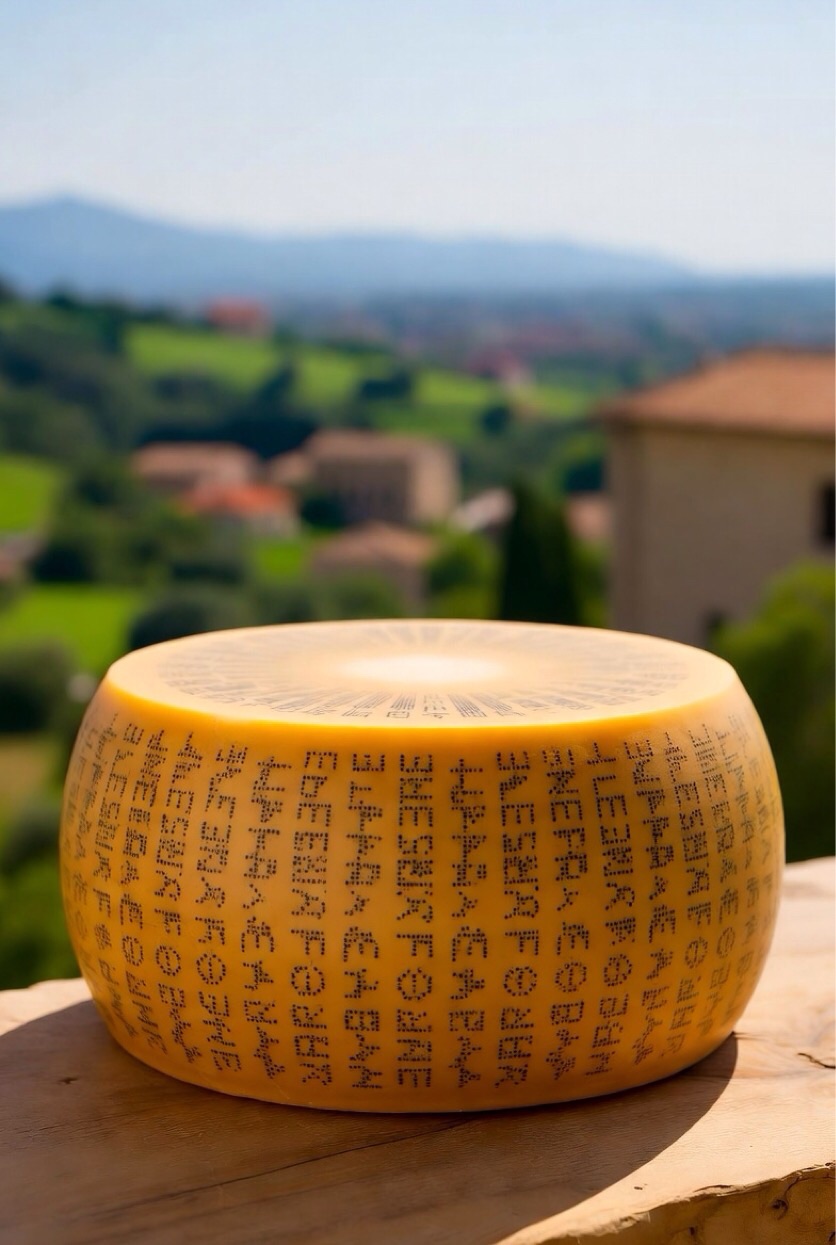

When you see “Parmigiano Reggiano” stamped on the rind… that is the real deal.

That name is protected by law (it’s called a PDO—Protected Designation of Origin). It means it can only be made in that one specific region of Italy, with those specific ingredients, using that 900-year-old method.

“Parmesan” is just a nickname. Here in Canada and the U.S., any company can make a hard, salty cheese, grind it up, put it in a shaker, and call it “Parmesan.” It’s not the same. It’s like comparing a fresh, wood-fired pizza from Naples to a frozen one from a box. Both exist, but they are not the same thing.

So yes, that wedge you buy at Costco with the “Parmigiano Reggiano” name and the pin-dots on the rind? You can feel good about that. You’re holding the authentic King of Cheeses.

Why Does It Cost So Much? (And What About That $70,000 Wheel?)

I’ve heard the wild rumors, too—that a wheel costs $70,000. Let’s be clear: for a normal, 24-month-old wheel, that’s just not true. A whole 80-pound wheel that a restaurant might buy costs more like $1,500 to $2,000. Still a ton of money, right?

So where does a number like $70,000 come from?

That’s not a price, that’s a world record. Those kinds of numbers only appear at high-profile charity auctions, like at the World Cheese Awards. A bidder might pay that much for a one-of-a-kind, ultra-rare wheel—maybe one that’s been aged for 20 or 25 years (most are aged 2-3). It’s a collector’s item, a piece of history, with the money going to a good cause.

For the rest of us, the high price is based on quality, not just hype. Here’s why:

- The Milk: It takes a ridiculous amount of milk. We’re talking about 250 gallons of the best, freshest, unpasteurized milk to make just two wheels.

- The People: This isn’t a factory assembly line. A master cheesemaker, the casaro, makes it by hand. After a full year of aging, an expert from the “Consorzio” (the cheese council) comes and taps every single wheel with a special hammer. They listen to the sound it makes to find any tiny flaw inside. Only the perfect wheels get the fire-branded seal of approval.

- The Time: This is the big one. The cheese must be babysat in a giant warehouse for at least one year. But the best ones sit for two, or even three years.

Think about that. As a chef, I have so much respect for this. You create something beautiful, and then you have to wait three years before you can even sell it. That’s not just a product; that’s a true labor of love.

You’re not just paying for cheese. You’re paying for time.

The Most Famous Recipe of All

You can’t talk about this cheese without talking about the original Fettuccine Alfredo.

Forget the thick, heavy cream sauce we know in North America. The original dish, made famous in Rome, had only three ingredients: fresh fettuccine, good butter, and an incredible amount of 24-month Parmigiano Reggiano.

The magic is all in the technique. You toss the piping hot pasta with the butter and cheese, adding a splash of the starchy pasta water. The heat melts the cheese and the fats emulsify with the water, creating a creamy, velvety sauce right before your eyes. It’s not a sauce you pour; it’s a sauce you create. It’s a hug in a bowl, and it’s a perfect celebration of the cheese itself.

A Final Thought

So next time you’re at the store, I hope you’ll look at that wedge of Parmigiano Reggiano a little differently. You’re not just buying an ingredient. You’re buying a 900-year-old story of passion, patience, and pure Italian magic.

🍳 Chef’s Recipes: Using The Right Age

As promised, here are some perfect ways to use this amazing cheese. The age of the wheel changes everything—its flavor, its texture, and what it’s best for.

- The Famous One: The Original Fettuccine Alfredo

This is the classic, pure and simple. The 24-month-old cheese is best here.

- Bring a large pot of water to a boil and salt it well.

- Cook fresh fettuccine pasta until al dente.

- In a large, warmed bowl, add a few generous pats of high-quality unsalted butter.

- Use tongs to transfer the hot pasta directly into the bowl (don’t drain it! You want that starchy water clinging to it).

- Add a massive handful (at least a cup) of finely grated 24-month Parmigiano Reggiano.

- Toss everything vigorously. Add a small splash of the hot pasta water and keep tossing. The butter and cheese will melt and emulsify with the water to create a stunningly creamy sauce that coats every strand. Serve immediately with extra cheese and fresh black pepper.

- The Young & Mild (12-18 Months)

This cheese is creamy and delicate. It’s best used where you want a subtle flavor that doesn’t overpower.

- Recipe Idea: Pear and Parmigiano Salad. Shave the cheese with a vegetable peeler over a bed of arugula. Add sliced fresh pears, toasted walnuts, and a simple lemon vinaigrette. The mild cheese complements the sweet pear without fighting it.

- The Gold Standard (24-30 Months)

This is your classic—nutty, savory, and perfectly crystalline. It’s the ultimate all-purpose flavor bomb.

- Recipe Idea: Classic Cacio e Pepe. The simplicity of this dish (pasta, black pepper, and cheese) demands a high-quality cheese. A 24-month Parmigiano melts into the pasta water to create a creamy, rich sauce that is nutty and perfectly salty. This is also the cheese to use for making a true Pesto alla Genovese.

- The Old & Bold (36+ Months)

This cheese is intense, complex, and very crumbly. It’s meant to be tasted on its own, not hidden.

- Recipe Idea: A “Chef’s Tasting” Bite. This cheese is the star. Break it into small, rustic crumbles. Serve them on a small plate and drizzle with a few drops of real, aged balsamic vinegar (the thick, syrupy kind) or a tiny bit of high-quality honey. It’s the perfect appetizer or dessert.

Stay Hungry my friends

Ciao !

Chef Bari

❤️ A Note From Chef Bari

If you enjoyed this post, please take a moment to support my work. Any of these ways (or all of them!) would without a doubt be very helpful and deeply appreciated:

• Buy Bari a Coffee – Click Here

• Purchase my cookbook, “Canadian Recipes of the Great White North“

• Purchase kitchen supplies through my affiliate: Canada Baking Supplies ( If you do purchase supplies from here, please let me know in comments below)

• And please, join me on INSTAGRAM

Thank you all!

Leave a Reply